This fall, Governor Cuomo signed a campaign pledge with Long Island State Senate Democratic candidates, many of whom won their elections, to make New York City bear greater responsibility for the subway and bus system’s capital needs. The campaign pledge was the continuation of a long-standing demand by the Governor that New York City contribute more toward the enormous costs of the MTA capital budget. He even suggested in his 2018 budget proposal that the City take full financial responsibility for the MTA New York City Transit capital plan, but it was not accepted by the Legislature at the time of budget adoption in April 2018.

The political candidates from Long Island may not have realized that, today, the Long Island Rail Road is the most heavily subsidized operation of the three transit systems, including New York City Transit and Metro North.

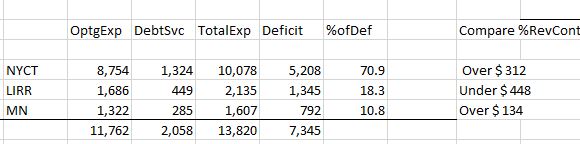

These excerpts from the new MTA budget, adopted in December, show that LIRR riders pay the lowest share of the respective operating budgets of the three systems.

Called the Fare Box Operating Ratio, the table shows the percentage of each system’s costs paid for by the fare and other basic operating revenue, like advertising. The data come from the MTA’s Dec. 2018 Adopted Budget, p.1-7,Vol.2.

The data show the LIRR Fare Box will contribute 43.4% of the LIRR’s operating costs in 2019 and decline to about 38% by 2022. New York City Transit’s fare provides 51.1% in 2019 and about 47% in 2022. Metro North riders contribute a higher share than either system.

The costs do not include debt service, where interest on borrowed funds for a huge construction project to link the LIRR to Grand Central Station, East Side Access, are located. The East Side Access’ final cost at completion, scheduled for 2022, will be $11 billion.

Is there a dollar figure that can be put on the LIRR’s higher loss ratio, compared to the other MTA systems? I have made an estimate that adds debt service to operating expenses, and then compares the proportions of farebox revenue each system contributes to the whole system, to the proportion each system contributes to the systemwide deficit.

First, one can look at the amount of fare and other revenue each part of the system contributes to the total system revenue. New York City Transit Fare revenue brings in $4.87 billion a year, 75% of total system revenue. The Long Island Rail Road brings in $790 million a year, about 12% of total system revenue.

Then one can compare the percentage of system revenue contributions with the deficits each part of the system experiences, and their respective portion of the whole system’s deficit.

This data analysis shows that the LIRR’s deficit is $1.345 billion a year (Total Expenses in 2d table – Revenue from 1st Table), and is more than 18% of the MTA’s total deficit. Its fare and other operating revenue, however, provides about 12% of the MTA’s total farebox revenue. The difference- 12% vs. 18%- amounts to an under-contribution by the Long Island Rail Road from its fare of $448 million more per year that has to be made up from taxes and subsidies, than the contributions of the other two systems to the total deficit. New York City Transit, by contrast, is about 71% of the system’s total deficit, but contributes 75% of total system fare revenue. NYC Transit fares are thus over-contributing $312 million a year more than its portion of the deficit, versus its revenue contribution.

New York City Transit’s numerical deficit, $ 5.2 billion, is far larger than the deficits of the other two systems, but that is not really an issue because the New York City economy is the main generator of the taxes and subsidies within the region that are used to subsidize the deficits.

The money to make up the system deficits comes overwhelmingly from a group of taxes enacted by the State Legislature and levied on the metropolitan region but not Upstate New York. Begun in the early 1980s and continued into the 21st century, the regional taxes include a payroll tax, a surcharge on corporate profits, a sliver of the sales tax, the mortgage recording tax, and a New York City stand-alone commercial real property transfer tax. The commuter rail systems and New York City Transit split about $590 million in surpluses from bridge and tunnel tolls about 60%-40% for the suburban systems pursuant to an early ’70s law. The State, City, and county governments contribute smaller amounts from their general funds.

The largest portions of these dedicated regional taxes come from from the City economy. About 75% of the wages paid within the region go to persons employed in New York City, according to 2017 data from the State Labor Department, and that compensation forms the base of the payroll tax, the largest of the dedicated taxes. A Rockefeller Institute of Government estimate of business profits from 2009 data showed nearly 78% of taxes from business profits in the region came from the City ( and the City is a larger share of the regional economy today than nine years ago). Revenue to the MTA from the surcharge on corporate profits is the second largest of the dedicated taxes.

One large dedicated tax to the MTA is the City’s commercial property transfer tax, which provides more than $600 million a year just to New York City Transit. Looking at where these streams of revenue come from leaves little doubt that taxes collected within the City are covering New York City Transit’s deficits and must, by logical extension, cover some of the LIRR’s deficits too.

The Governor justifies his demands that the City cover more system cost by citing a 1953 law that created the New York City Transit Authority and required the City to cover its capital costs (with limits). With cost estimates of the MTA’s next capital plan and NYC Transit Byford’s Fast Forward Plan reaching $40-$60 billion, who should pay for this is an important question.

But the answer is embedded in the tax history just described.

As the transit system deteriorated during the New York City-New York State financial crisis of the ’70s, Governor Carey and the Legislature devised a solution to the problem of the city’s obligation to cover NYC Transit’s capital costs. That solution was the set of dedicated taxes listed above, the enactment of which began in 1981-82.

Since the City only has the power to increase the property tax and has many basic governmental obligations already (schools, police, social welfare), the City would have needed the Legislature to allow it to levy a group of special new taxes to cover the transit system’s costs at that time. The Legislature just required the region’s residents and businesses to do this indirectly – pay new taxes going to the MTA- which the City and other local governments would have had to do directly- levy new taxes for the same purpose – with permission from the Legislature. If the City was forced to contribute billions in new revenue to the transit system today, the same problem would repeat itself. It would need to get permission from the Legislature for new taxes. Otherwise, funding for the basics like schools, cops, sheltering the homeless, etc., could be seriously impaired.

The net effect of the regional taxes was that New York City residents and businesses continued financial responsibility for the system because most of the taxes collected came from the City and paid for New York City Transit. The taxes collected from the suburbs contributed to the commuter rail system, except that the LIRR’s riders don’t cover a proper share of that system’s costs and get subsidized from taxes collected from the remainder of the region.

Sources of Information: Debt Service: Vol.2,Sect.2,pp.75-76, MTA Nov.Financial Plan

Debt service was allocated between LIRR and MN according to the ratio of each to total depreciation for the two. Depreciation data are found for LIRR and MN in Vol.2,Sect.5,p.72 and p.127, respectively.

0 comments on “LIRR’s Heavy Subsidies and the Coming Debate Over MTA Funding”